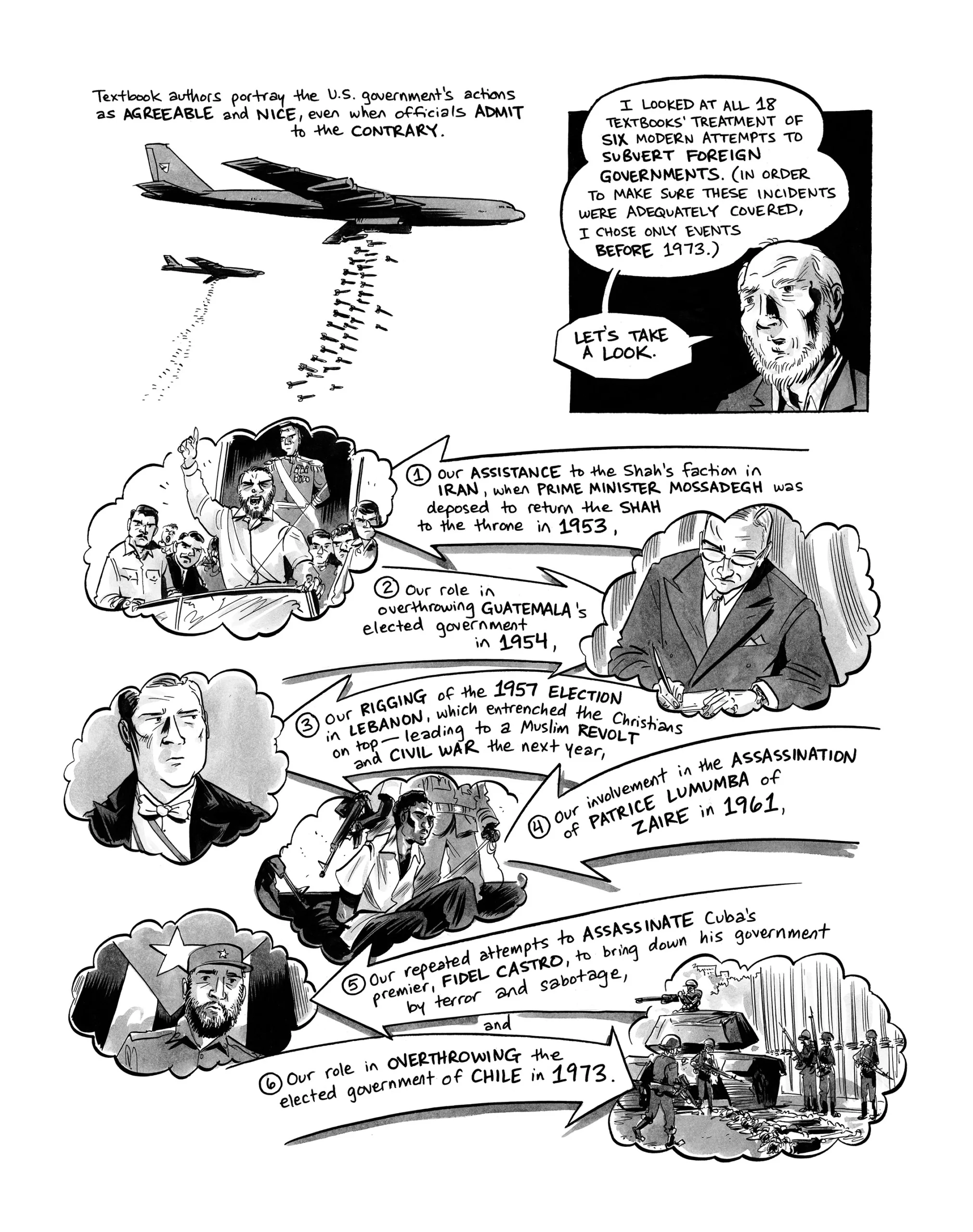

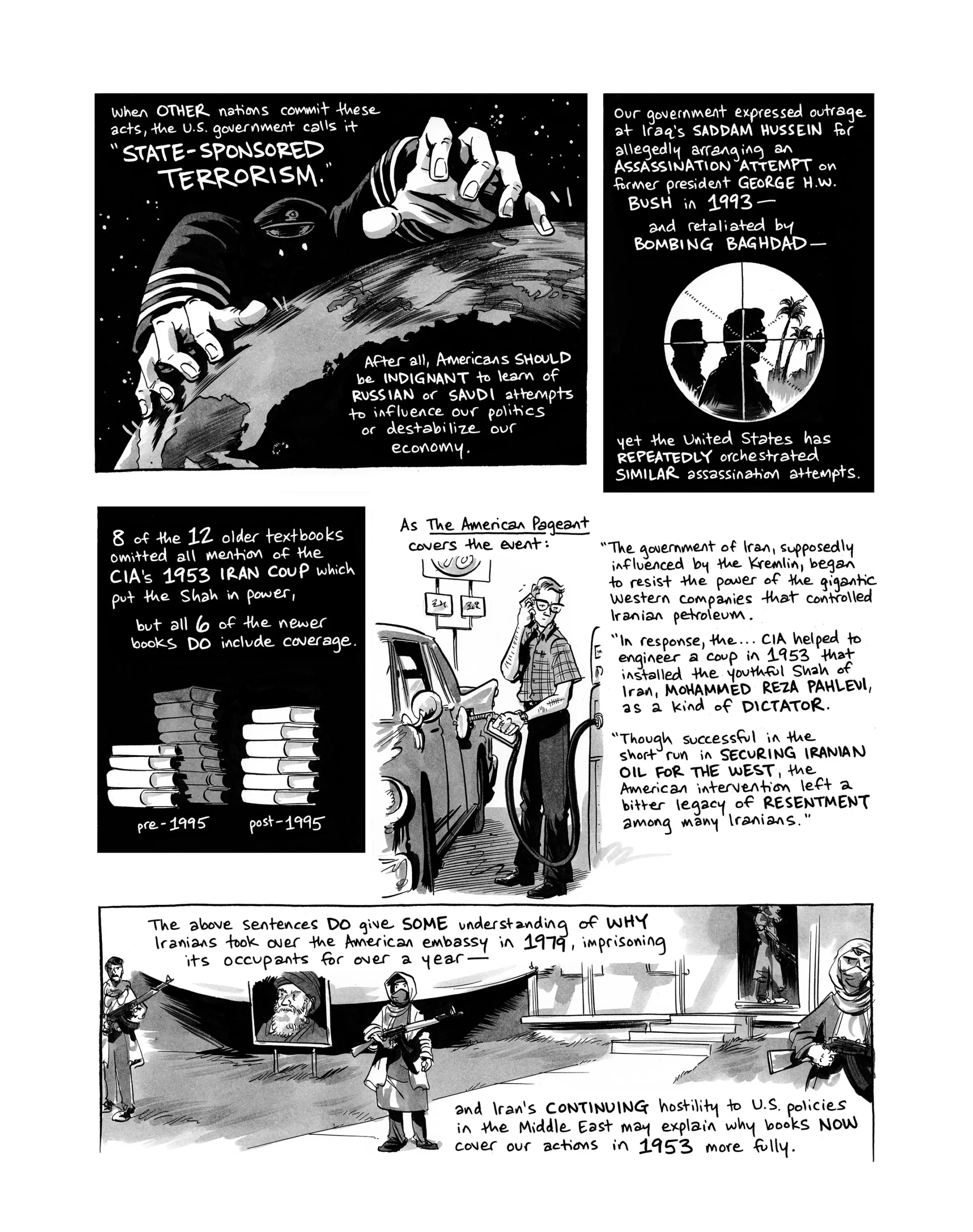

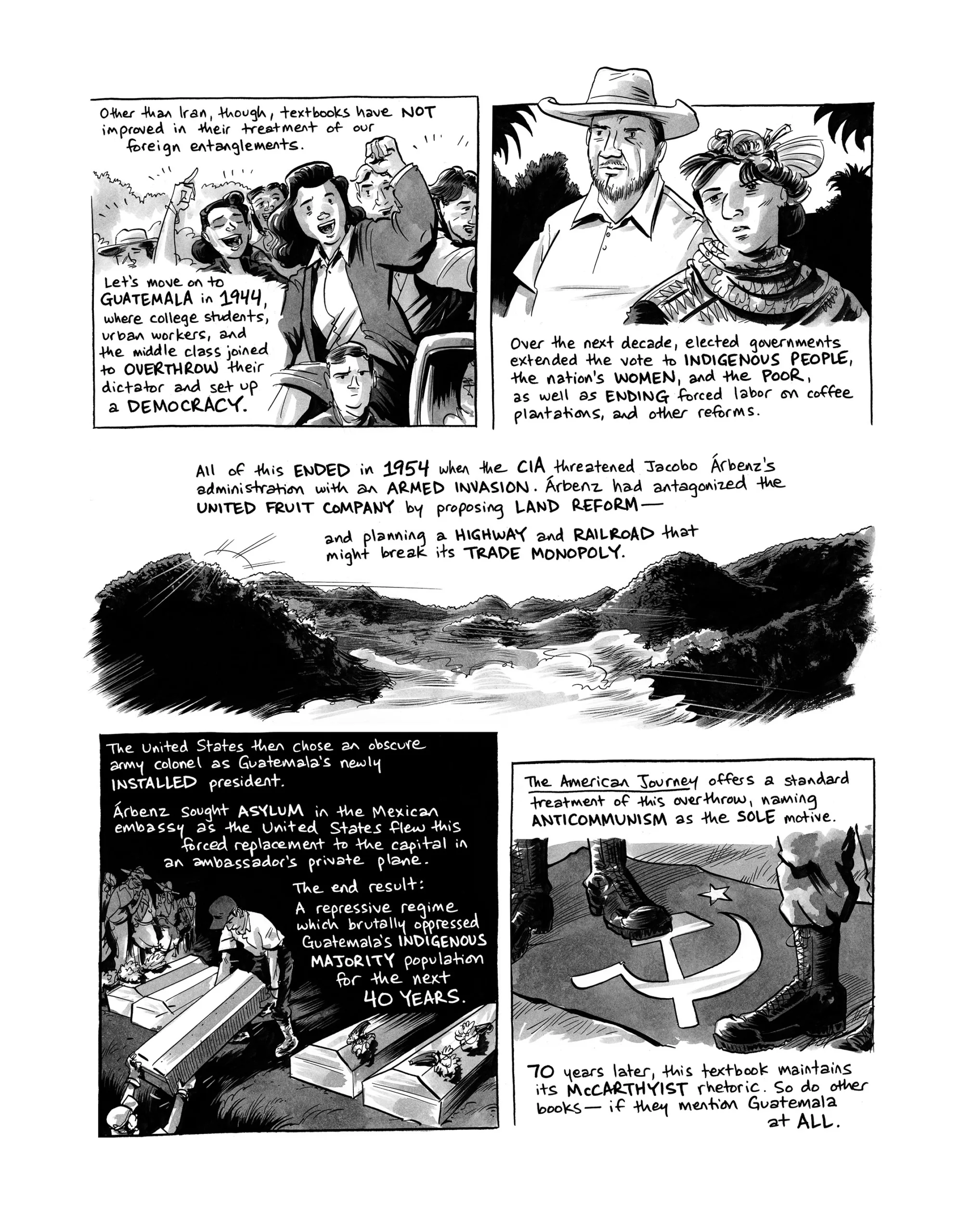

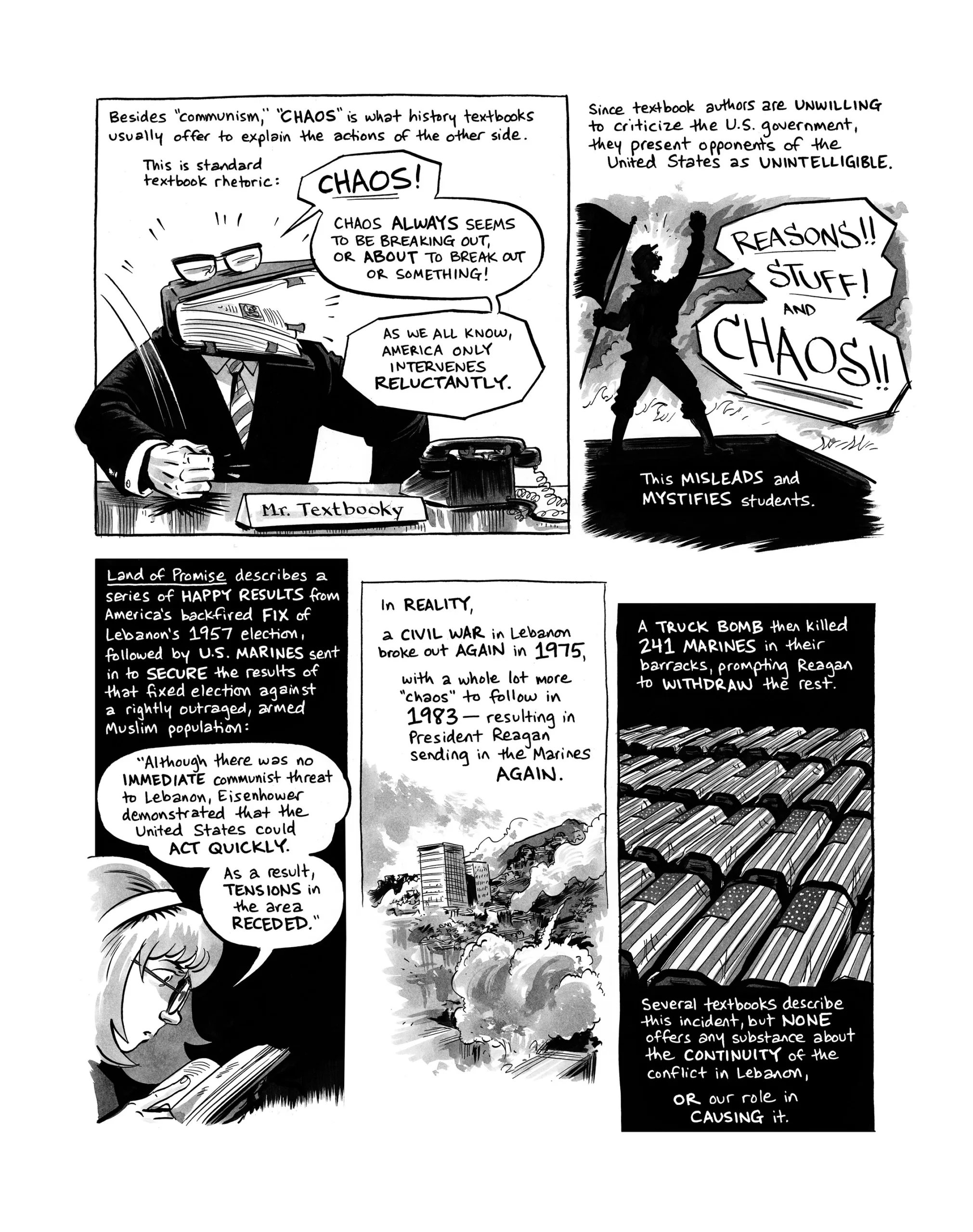

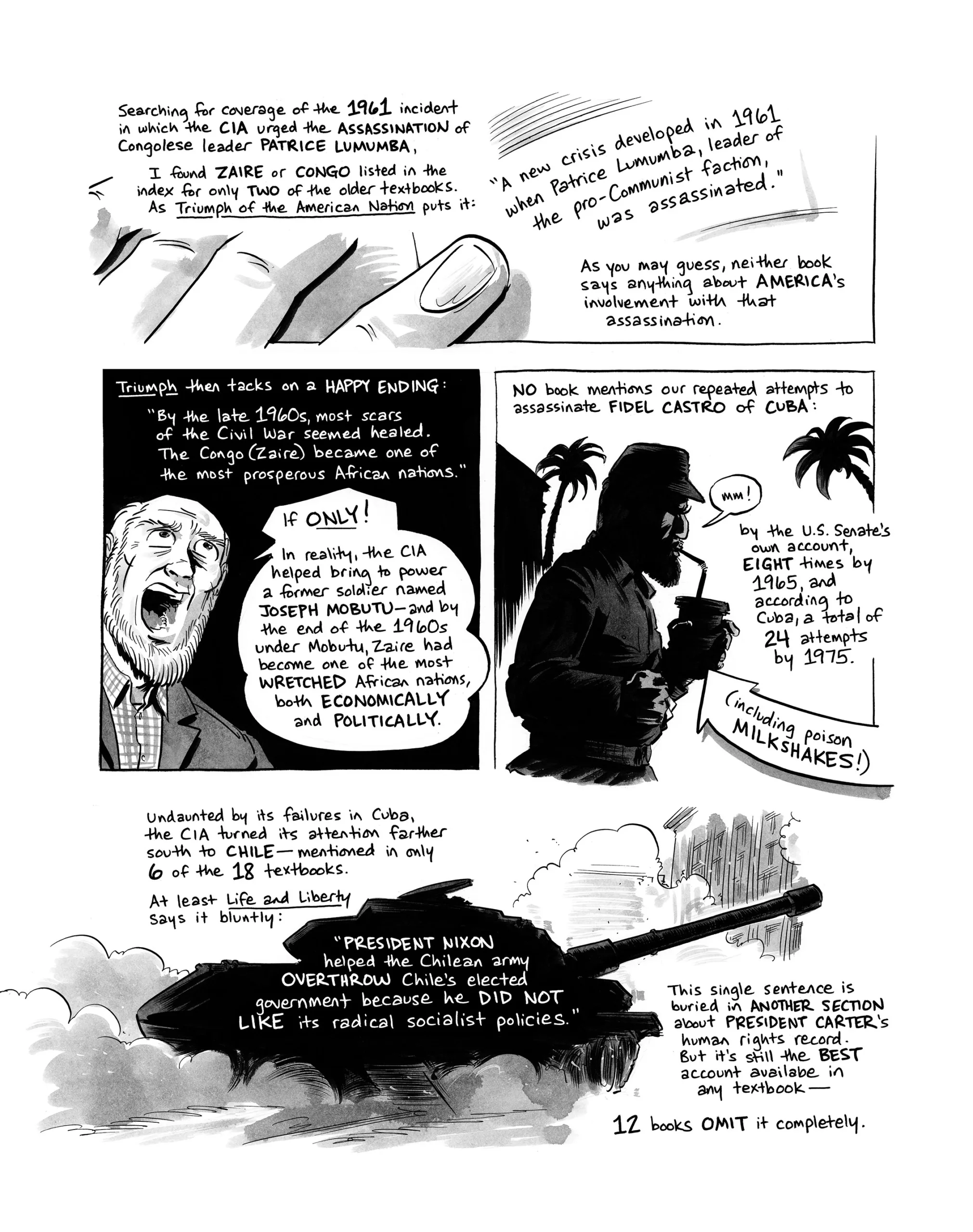

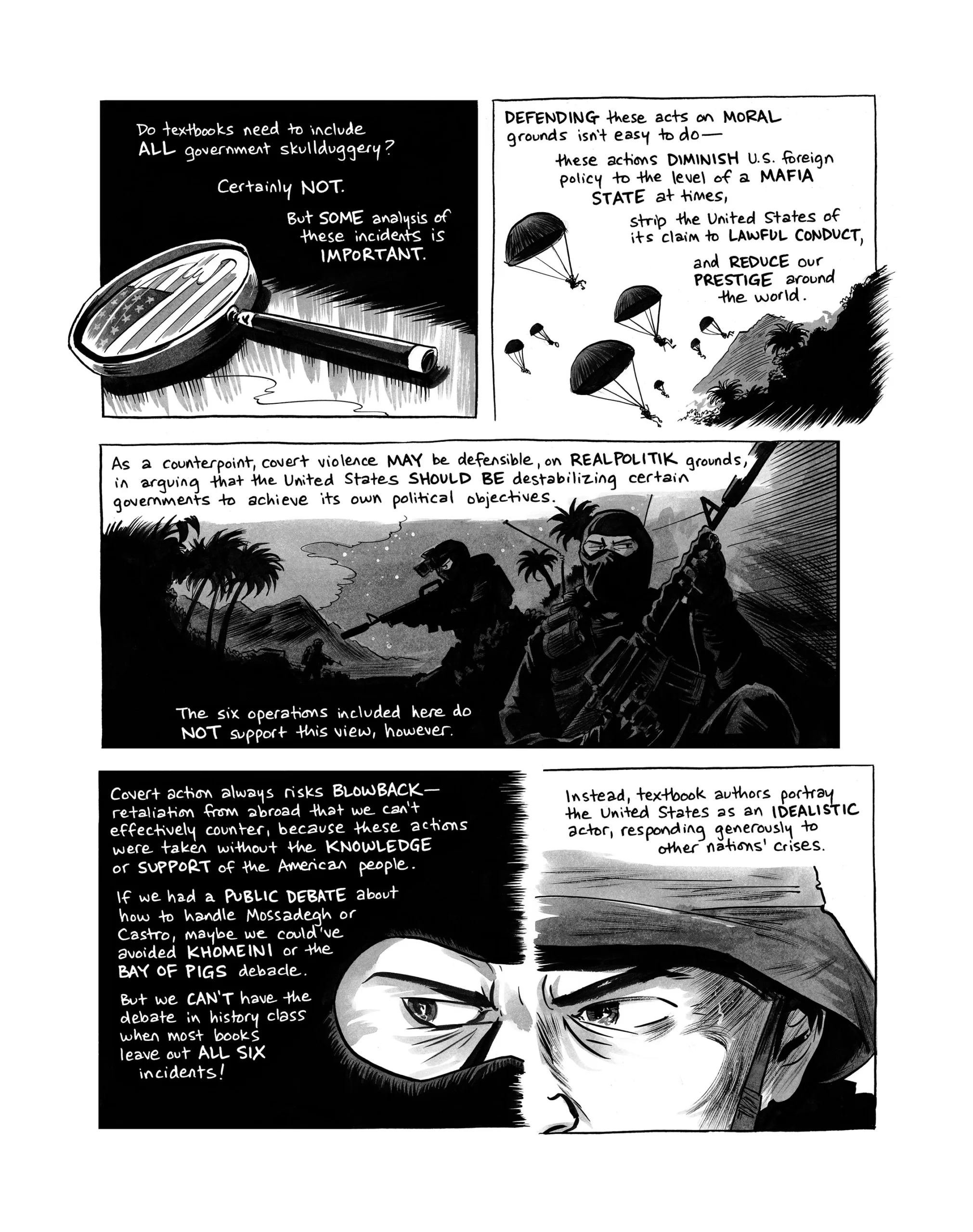

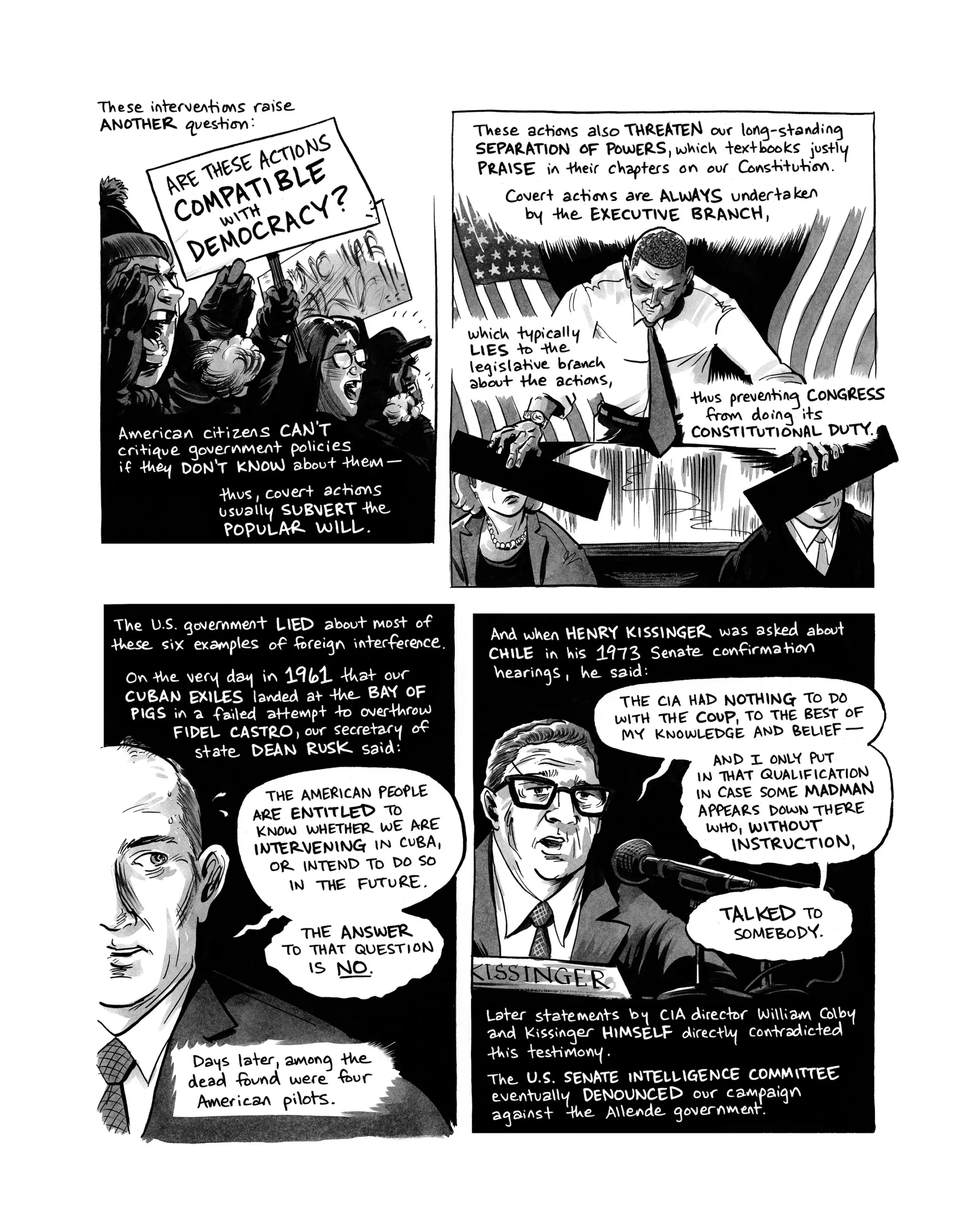

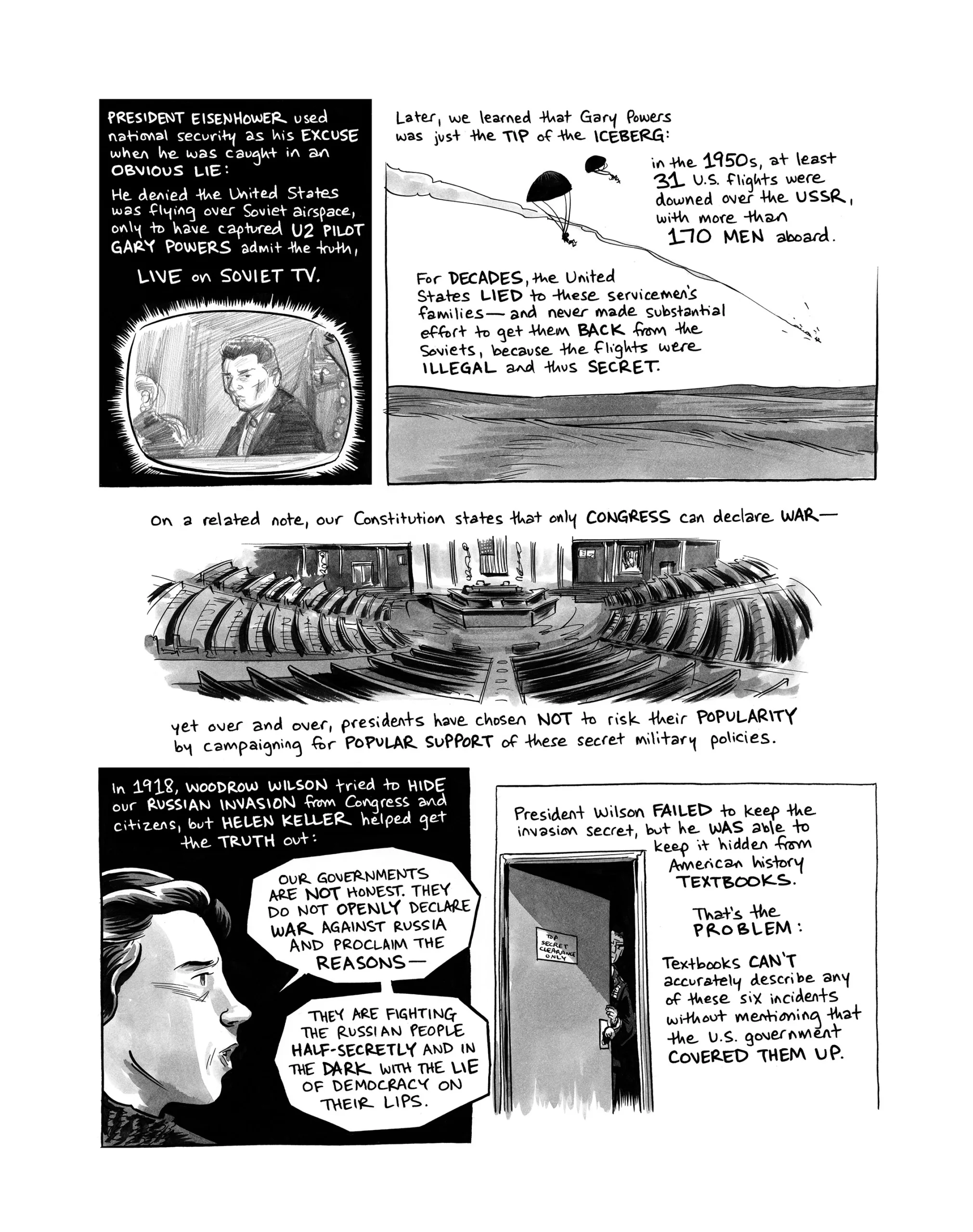

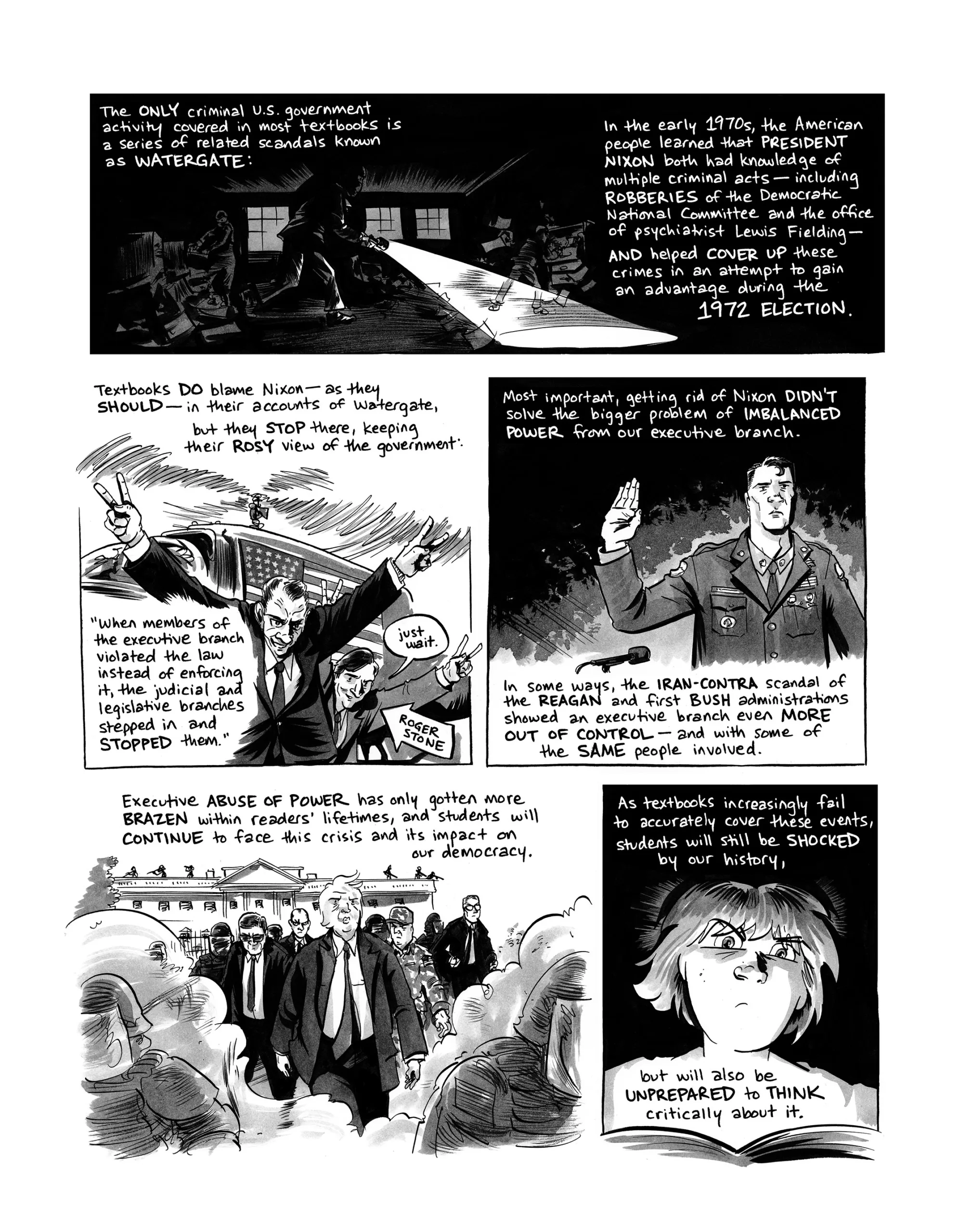

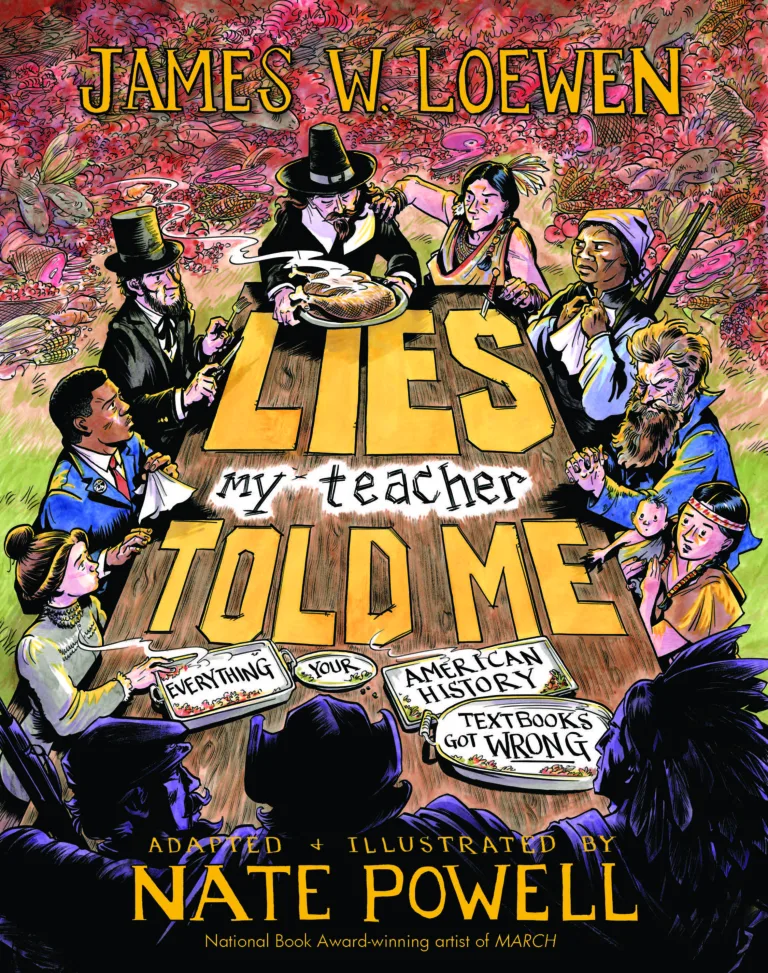

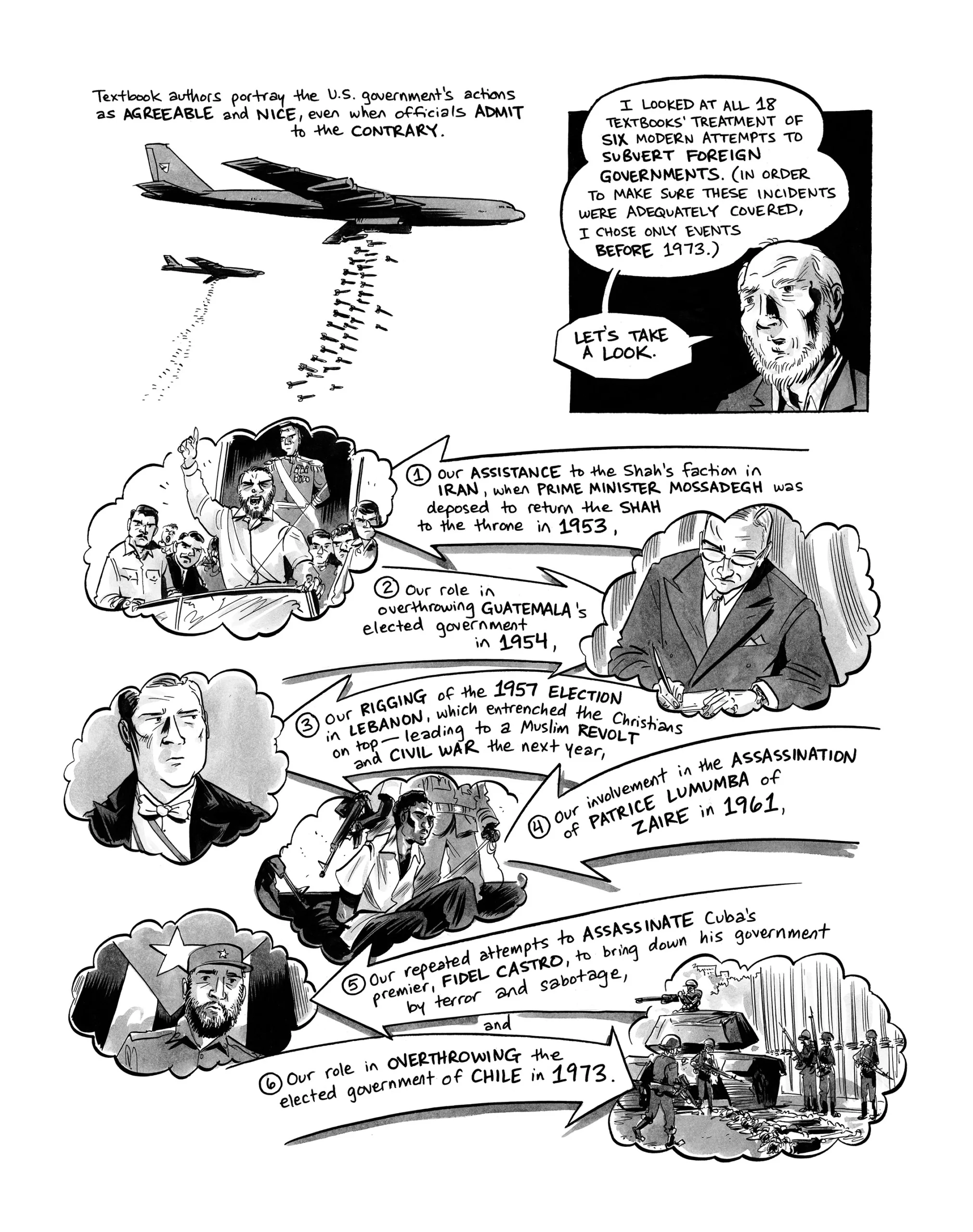

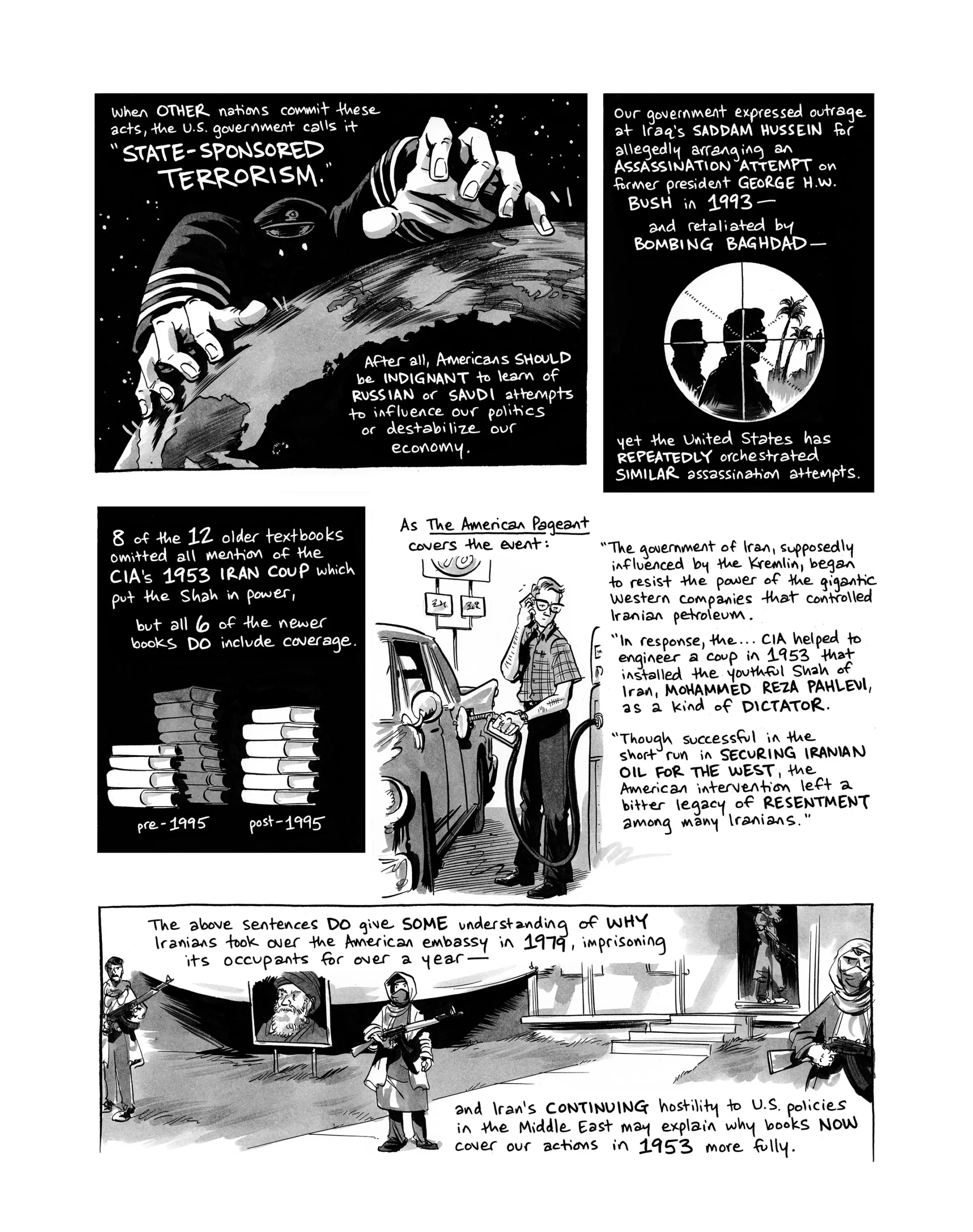

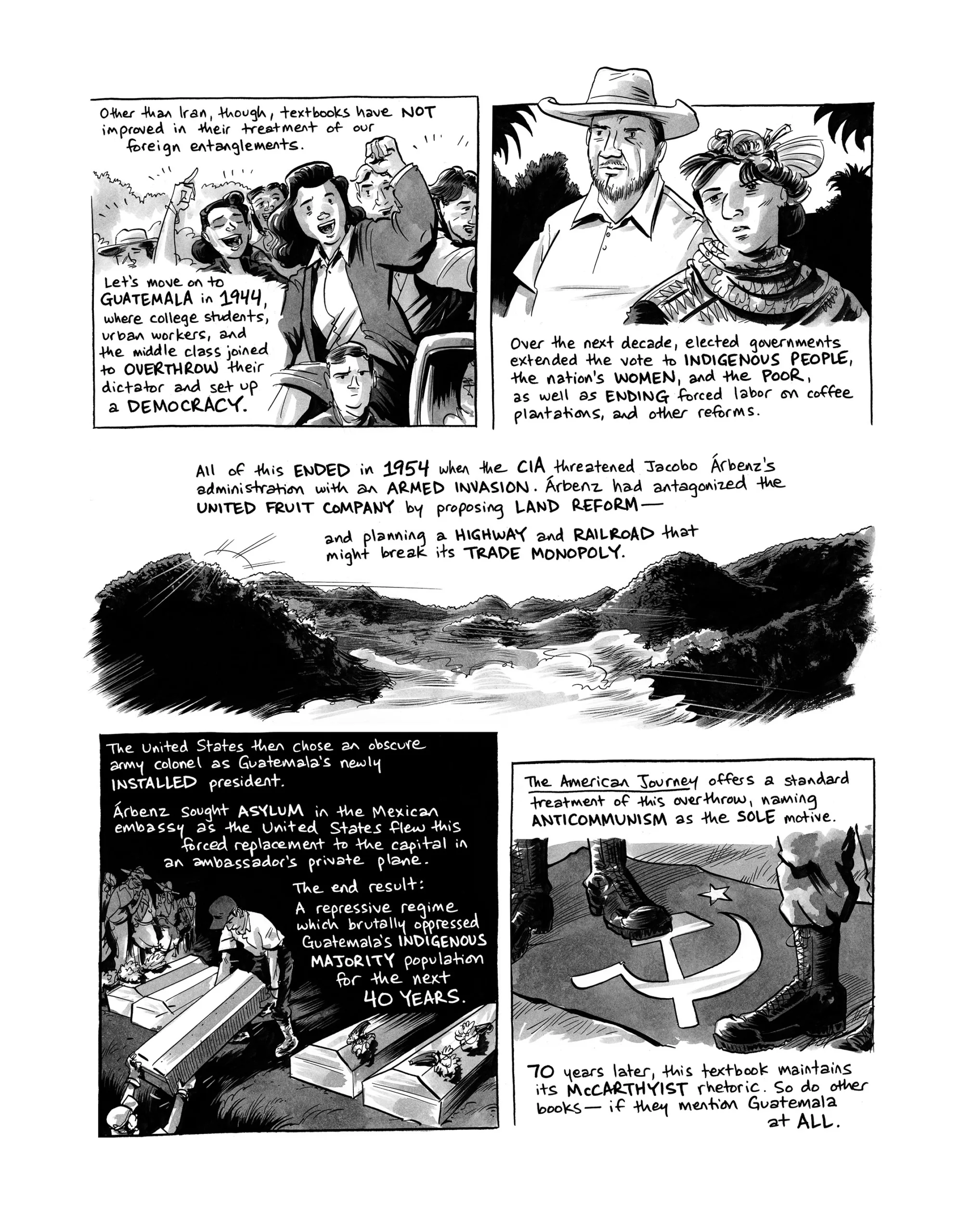

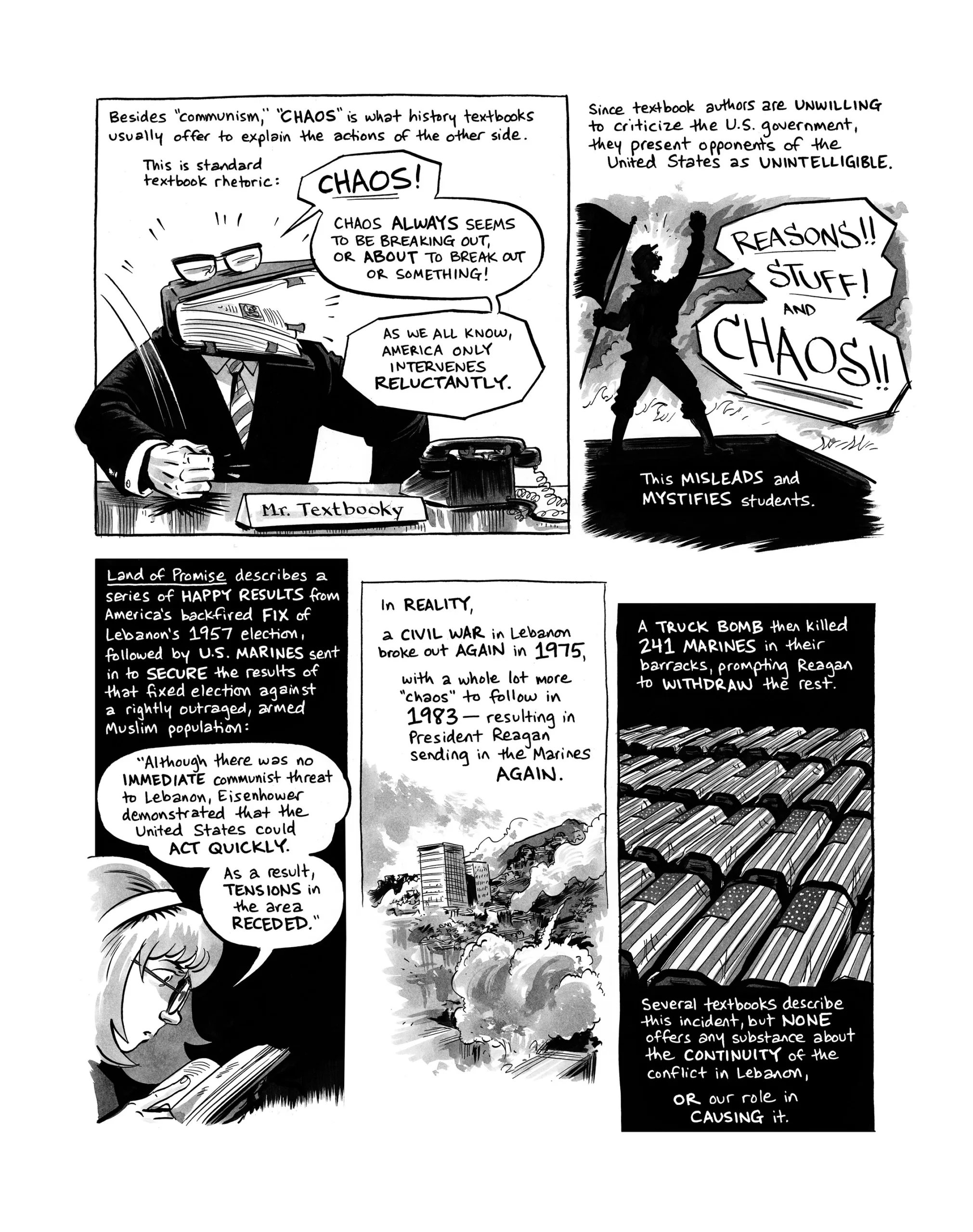

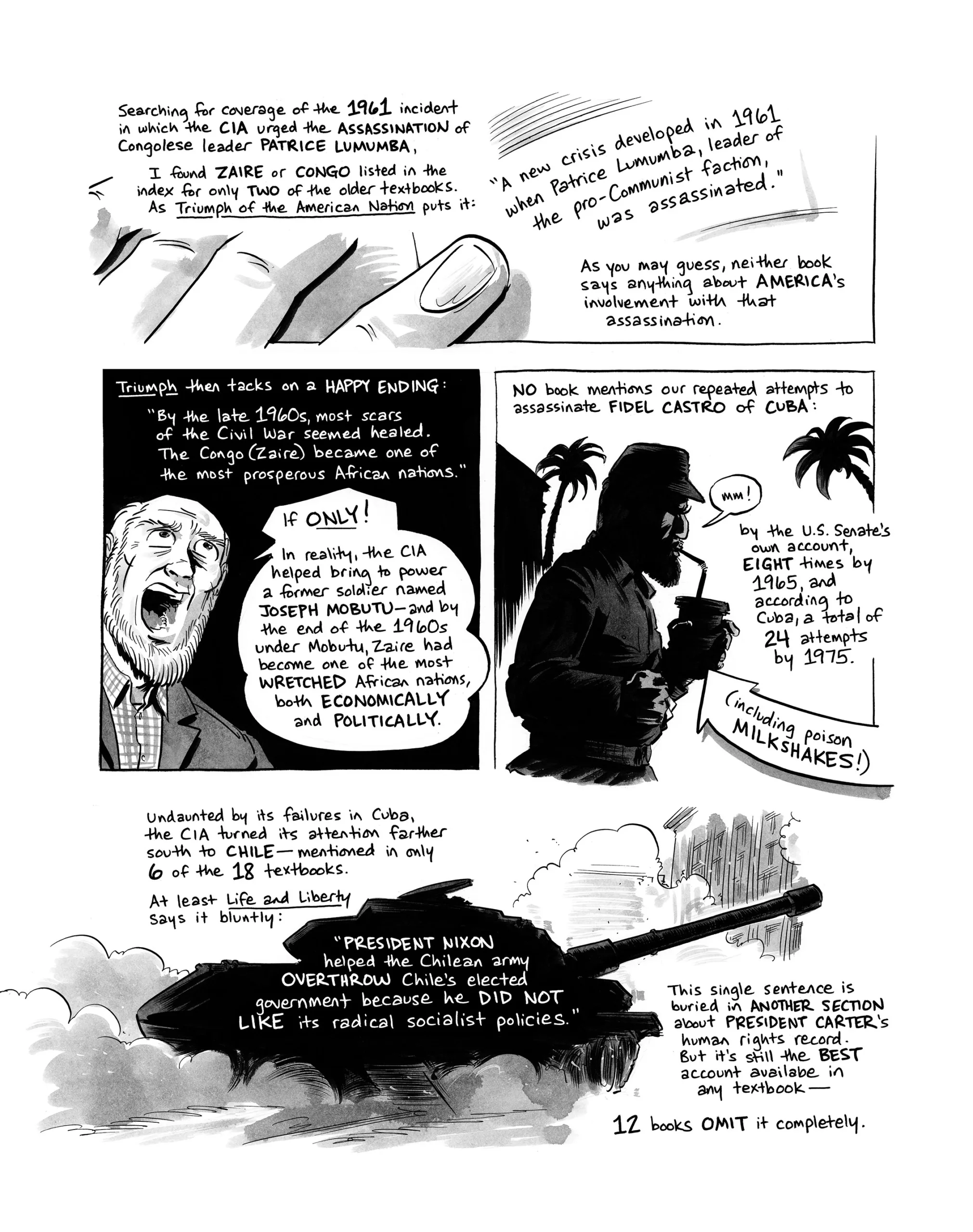

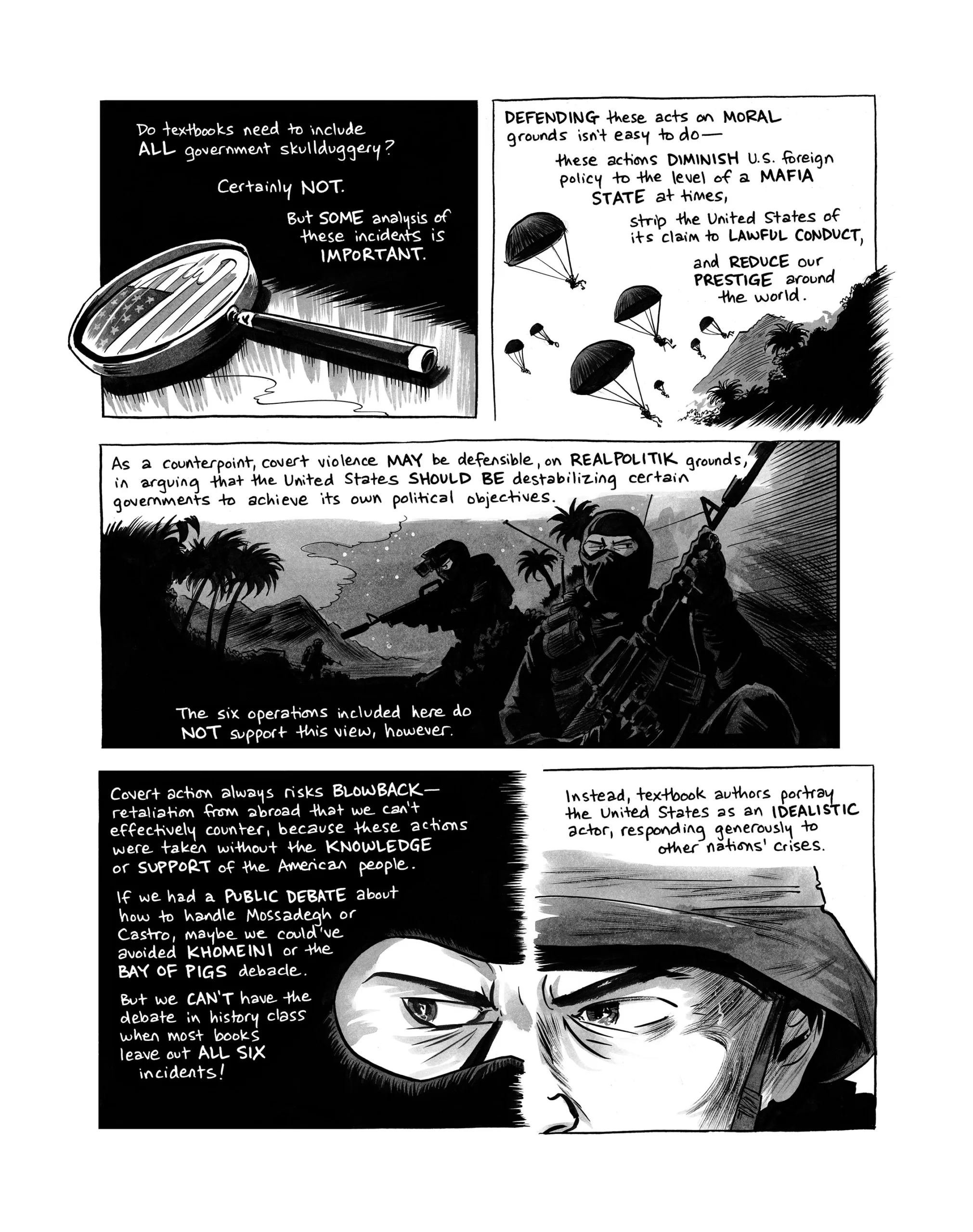

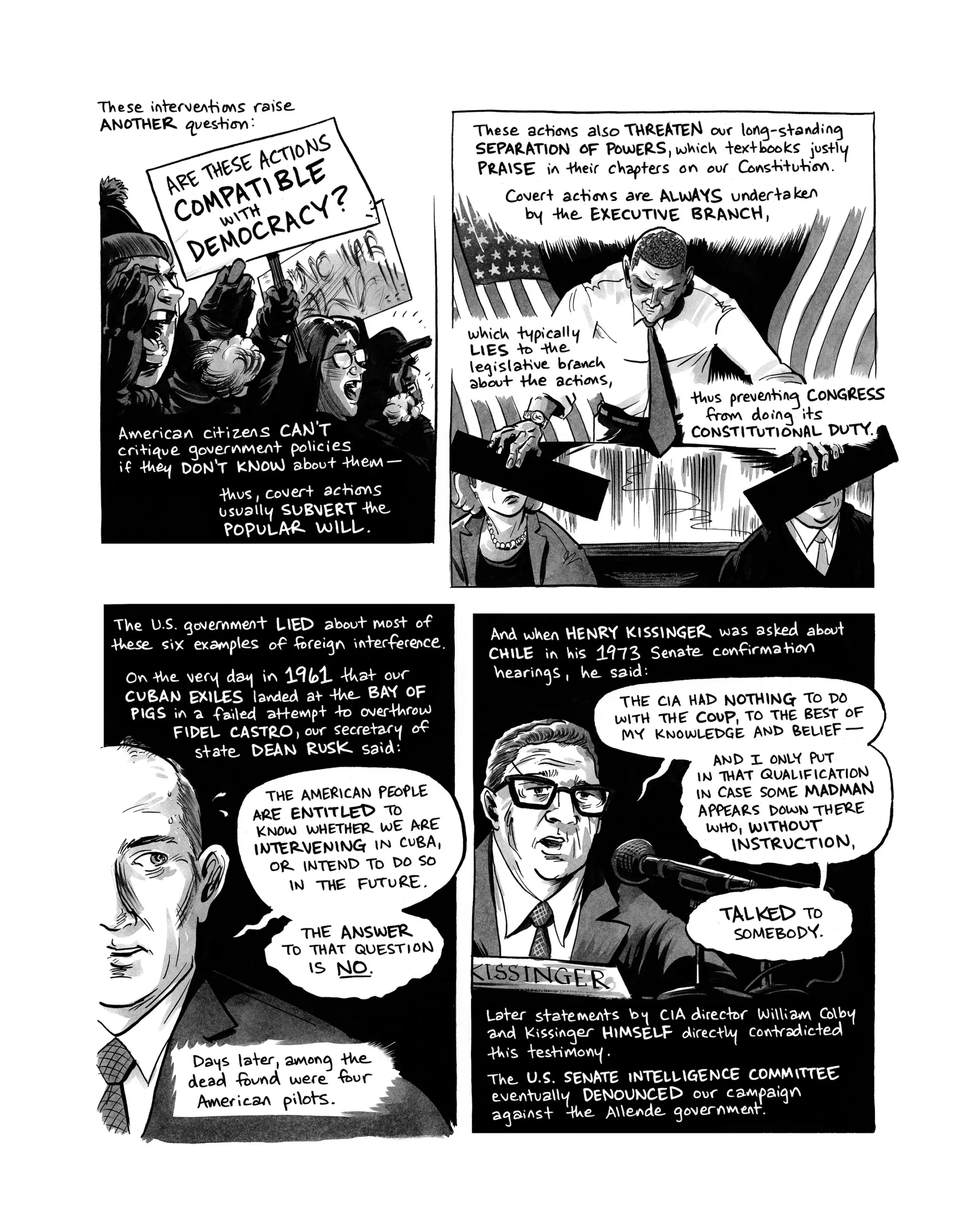

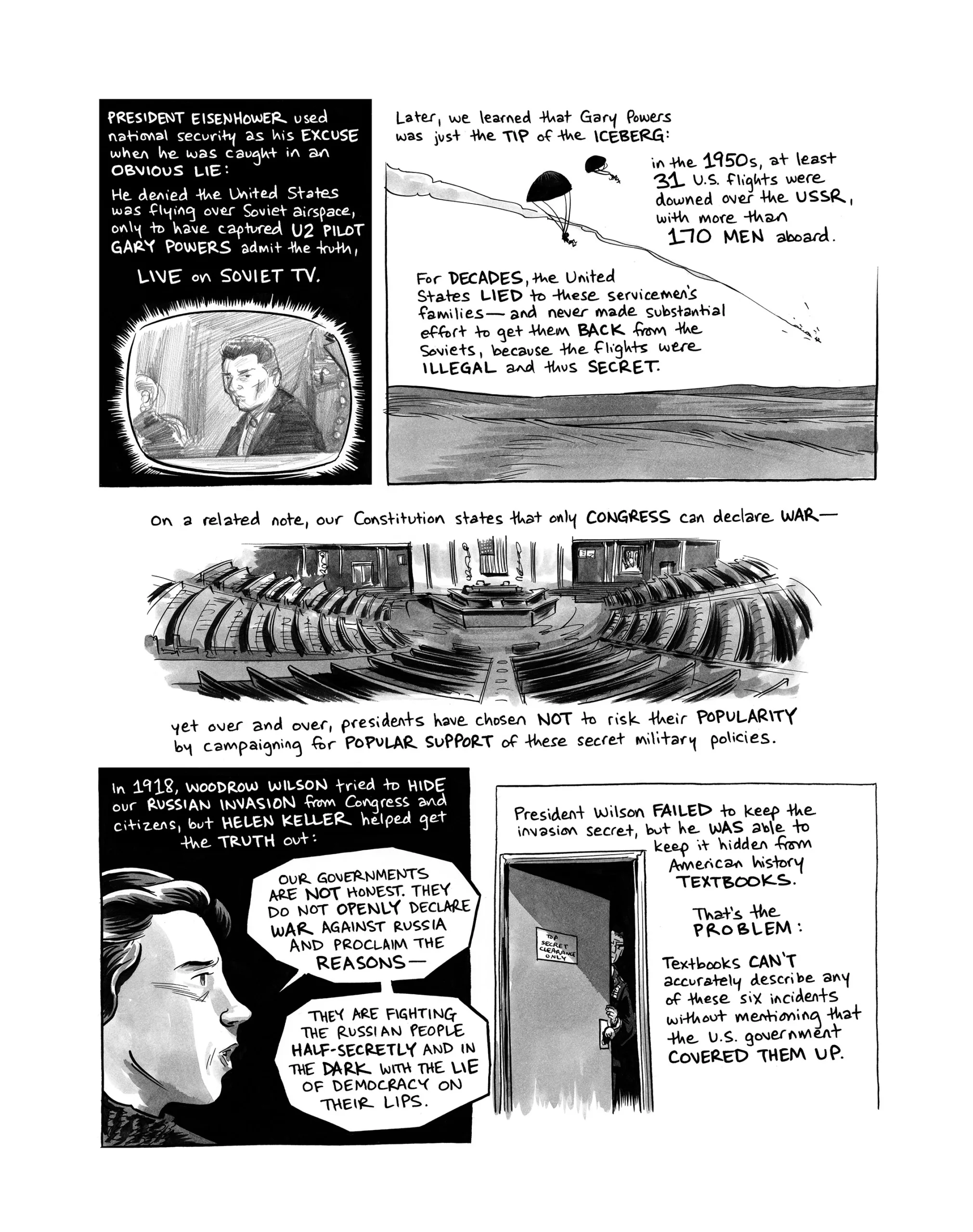

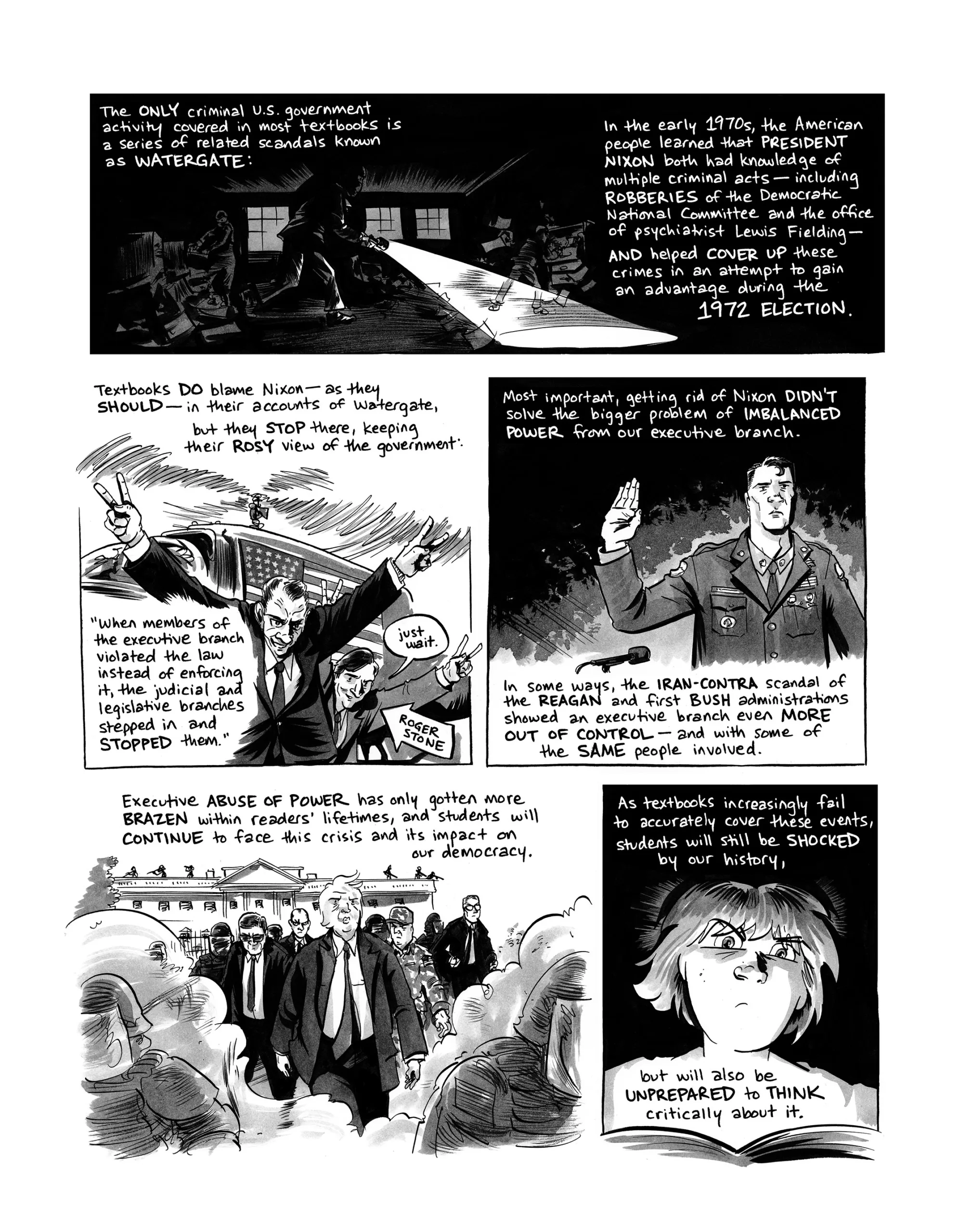

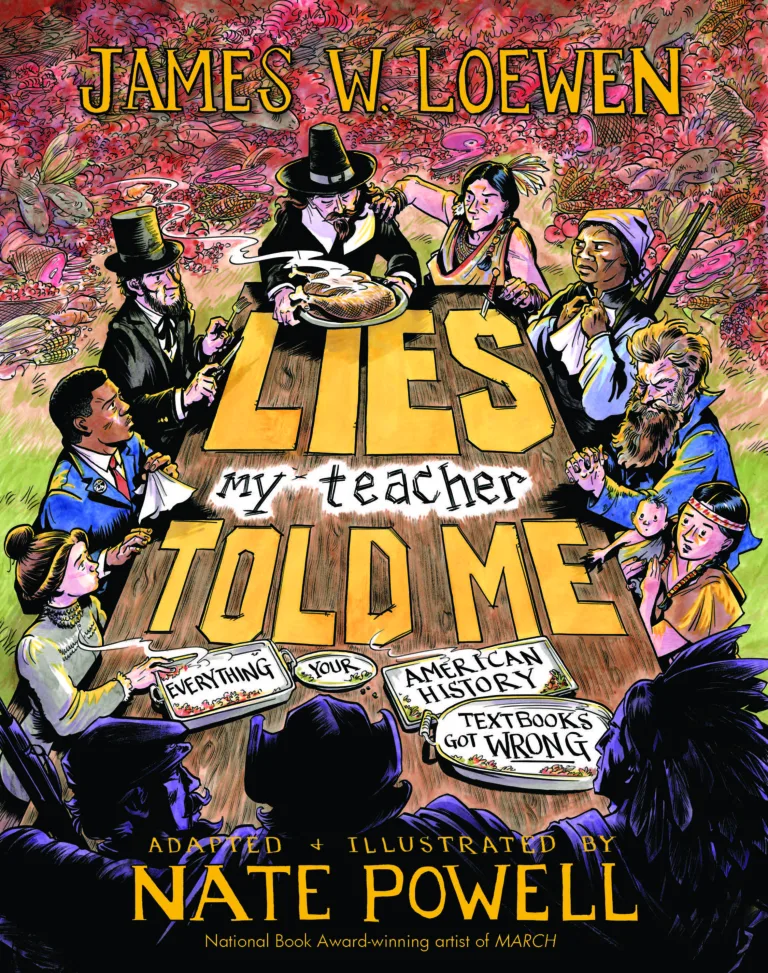

This is an excerpt from the book Lies My Teacher Told Me by James W. Loewen, adapted into comics by Nate Powell. The book critically examines how 18 current textbooks analyze incidents from U.S. history.

Check out Lies My Teacher Told Me.

This is an excerpt from the book Lies My Teacher Told Me by James W. Loewen, adapted into comics by Nate Powell. The book critically examines how 18 current textbooks analyze incidents from U.S. history.

Check out Lies My Teacher Told Me.