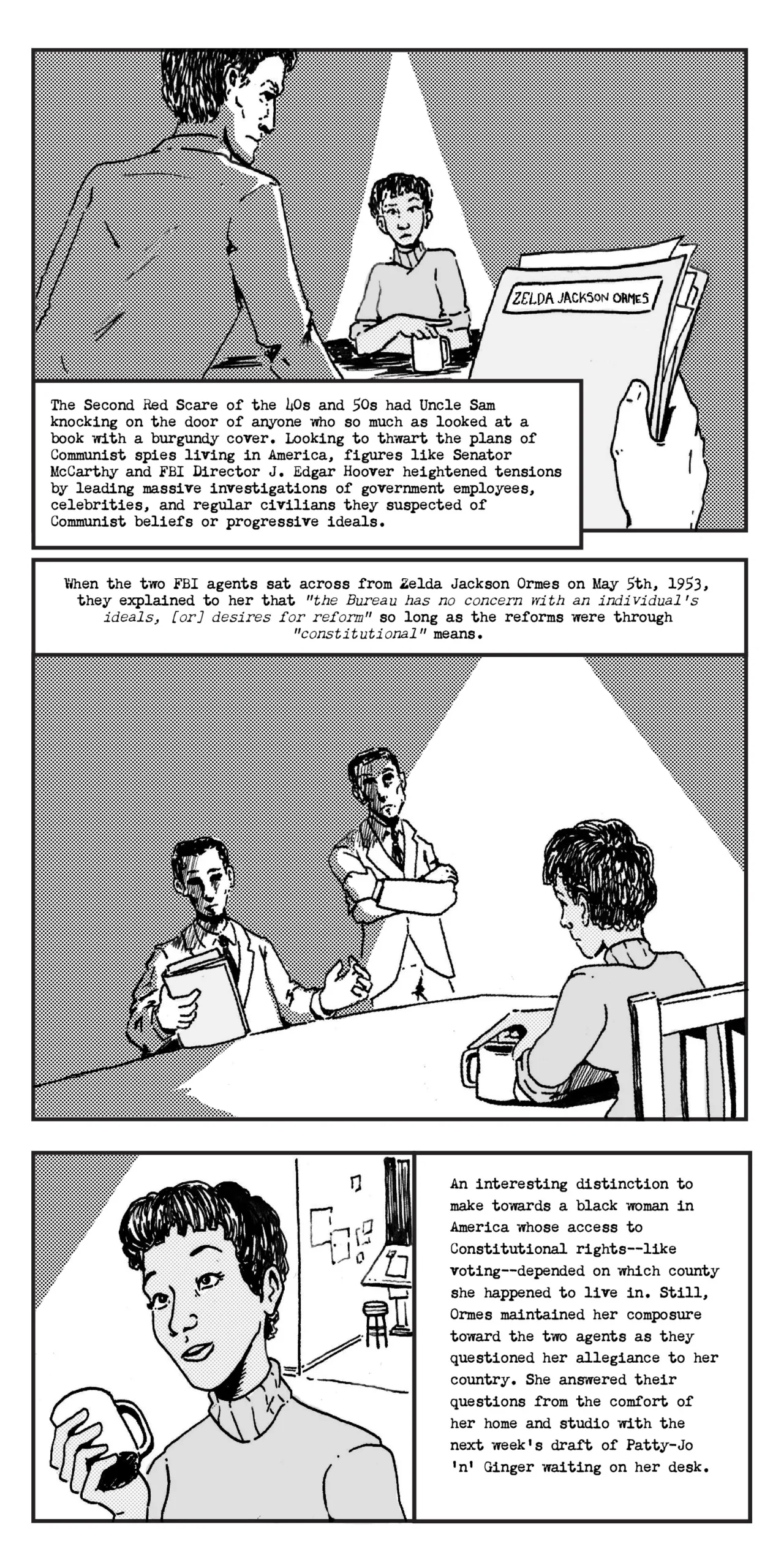

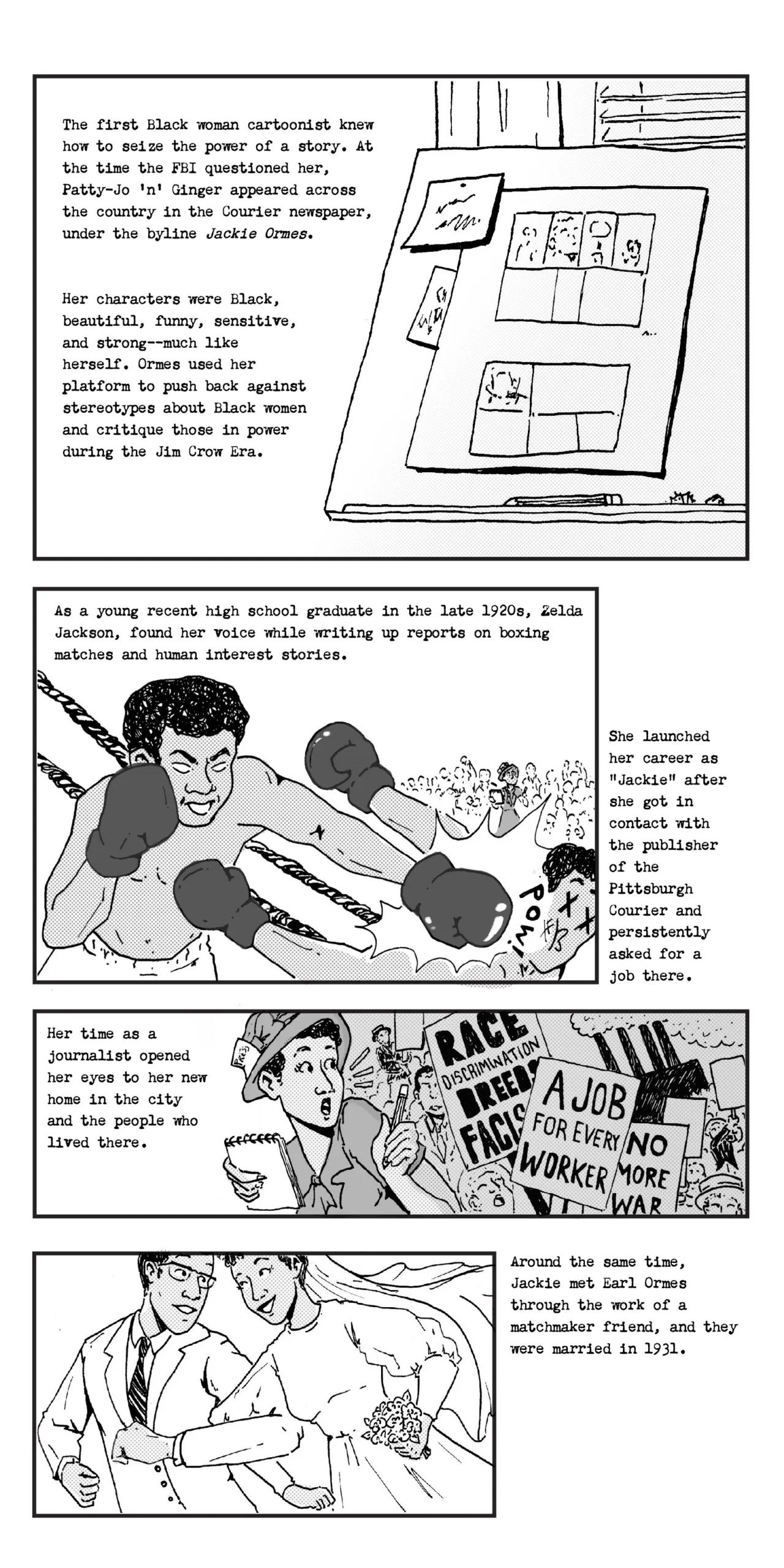

![Jackie Ormes typing at a typewriter in a busy newsroom at the Chicago Defender Towards the end of the strip's run and after living near her husband’s family in Ohio for a few years, the couple moved out to Chicago to join the rising, bustling, black community there. Jackie Ormes once again walked right into the newsroom of The Defender and got hired on the spot. She was a writer and reporter formally and worked outside that scope as a cartoonist from the 40s onward. Recreation Patty Jo comic Despite having a light enough complexion to pass as white, Ormes was committed to the black struggle and black representation in her art. That’s why in 1945 she started up with Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger, a one-panel-a-week series that followed a spunky little girl named Patty Jo and her patient sister older Ginger. Patty would make an observation like, [ It’s a letter to my congressman…i wanta get it straight from Washington…just which is the “American Way” of life, New York or Georgia???]. Ginger would react with a head shake or a nod or a side glance.](https://www.crucialcomix.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/JackieOrmes-Final-05-1-scaled.webp)

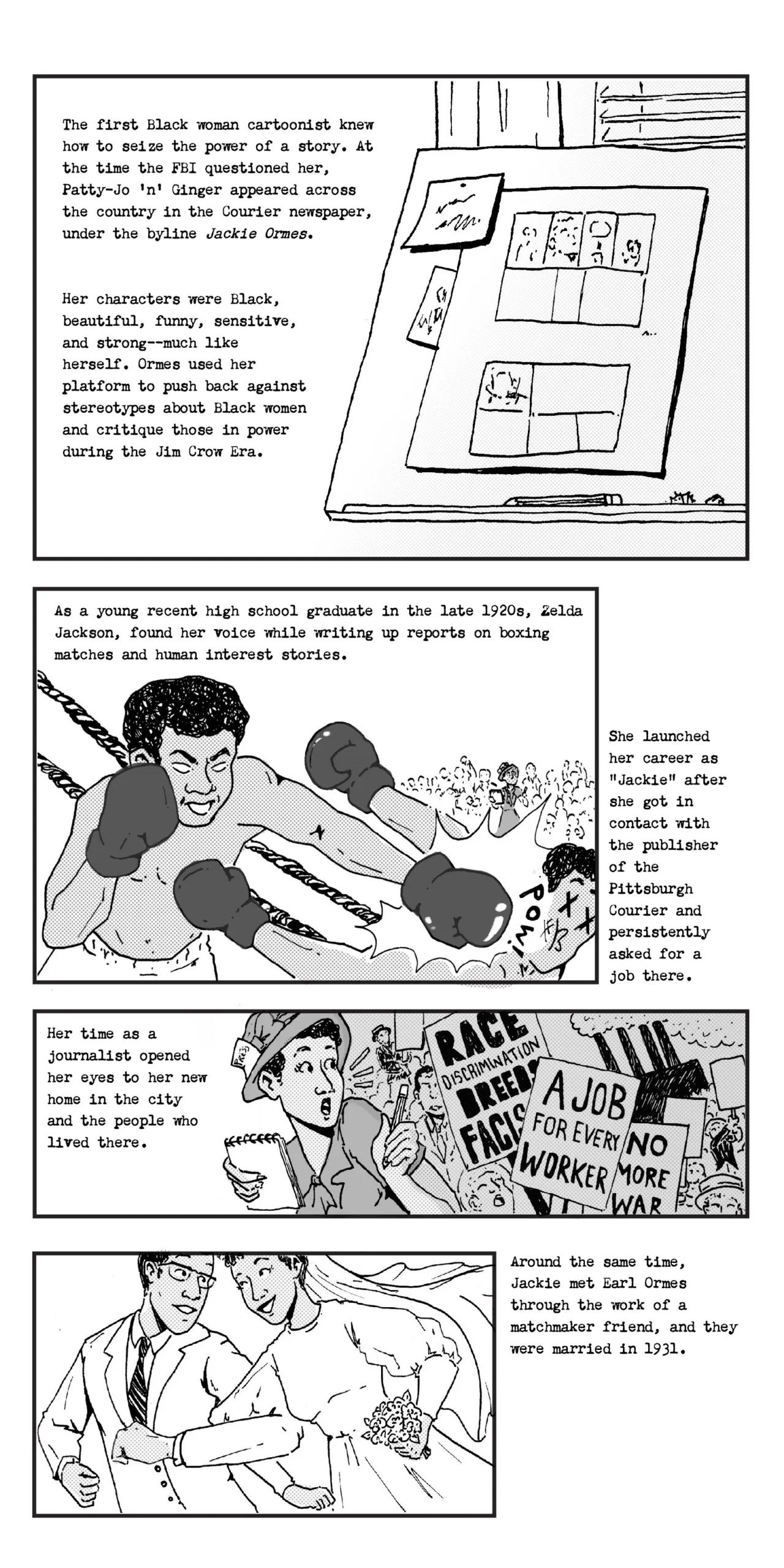

![Jackie Ormes lovingly painting Patty Jo Doll's face In 1947, Ormes took on a new venture: creating a Black doll for kids to play with. The usual Black dolls of the time perpetuated stereotypes. Those narratives were beginning to be called out, specifically how they affected children. “An article in Playthings, a toy industry journal, stated in 1909, ‘One of the chief demands for negro dolls comes from little white girls who desire these dark playmates to be used as servants…as maids, coachmen, butlers and the like… the children themselves [black children] do not seem to want them.’” - (Goldstein p 161 – “Negro Dolls,” Playthings, June 1909, 67) Panel 1: A young black boy points towards a white baby doll. A checkmark and an x stand in for the child’s opinion. Ormes noticed this trend around the same time that Dr. Kenneth Clark and Dr. Mamie Clark were conducting the famous Doll Test. In the experiment, the couple asked black children to choose and explain their reasoning as to which they preferred: a white baby doll or a black baby doll. The experiment in the 40s examined how age and skin tone played into the children’s perception of the dolls and by extension themselves. Lighter-skinned children wanted to see themselves as the white dolls which they viewed as “pretty” and “clean”. Darker-skinned children grew upset upon realizing that they saw themselves as black dolls which they viewed as ugly.](https://www.crucialcomix.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/JackieOrmes-Final-07-scaled.webp)

This comic was created through Crucial Comix's editing program. Ari Yarwood and Al Benbow edited this comic.

![Jackie Ormes typing at a typewriter in a busy newsroom at the Chicago Defender Towards the end of the strip's run and after living near her husband’s family in Ohio for a few years, the couple moved out to Chicago to join the rising, bustling, black community there. Jackie Ormes once again walked right into the newsroom of The Defender and got hired on the spot. She was a writer and reporter formally and worked outside that scope as a cartoonist from the 40s onward. Recreation Patty Jo comic Despite having a light enough complexion to pass as white, Ormes was committed to the black struggle and black representation in her art. That’s why in 1945 she started up with Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger, a one-panel-a-week series that followed a spunky little girl named Patty Jo and her patient sister older Ginger. Patty would make an observation like, [ It’s a letter to my congressman…i wanta get it straight from Washington…just which is the “American Way” of life, New York or Georgia???]. Ginger would react with a head shake or a nod or a side glance.](https://www.crucialcomix.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/JackieOrmes-Final-05-1-scaled.webp)

![Jackie Ormes lovingly painting Patty Jo Doll's face In 1947, Ormes took on a new venture: creating a Black doll for kids to play with. The usual Black dolls of the time perpetuated stereotypes. Those narratives were beginning to be called out, specifically how they affected children. “An article in Playthings, a toy industry journal, stated in 1909, ‘One of the chief demands for negro dolls comes from little white girls who desire these dark playmates to be used as servants…as maids, coachmen, butlers and the like… the children themselves [black children] do not seem to want them.’” - (Goldstein p 161 – “Negro Dolls,” Playthings, June 1909, 67) Panel 1: A young black boy points towards a white baby doll. A checkmark and an x stand in for the child’s opinion. Ormes noticed this trend around the same time that Dr. Kenneth Clark and Dr. Mamie Clark were conducting the famous Doll Test. In the experiment, the couple asked black children to choose and explain their reasoning as to which they preferred: a white baby doll or a black baby doll. The experiment in the 40s examined how age and skin tone played into the children’s perception of the dolls and by extension themselves. Lighter-skinned children wanted to see themselves as the white dolls which they viewed as “pretty” and “clean”. Darker-skinned children grew upset upon realizing that they saw themselves as black dolls which they viewed as ugly.](https://www.crucialcomix.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/JackieOrmes-Final-07-scaled.webp)

This comic was created through Crucial Comix's editing program. Ari Yarwood and Al Benbow edited this comic.

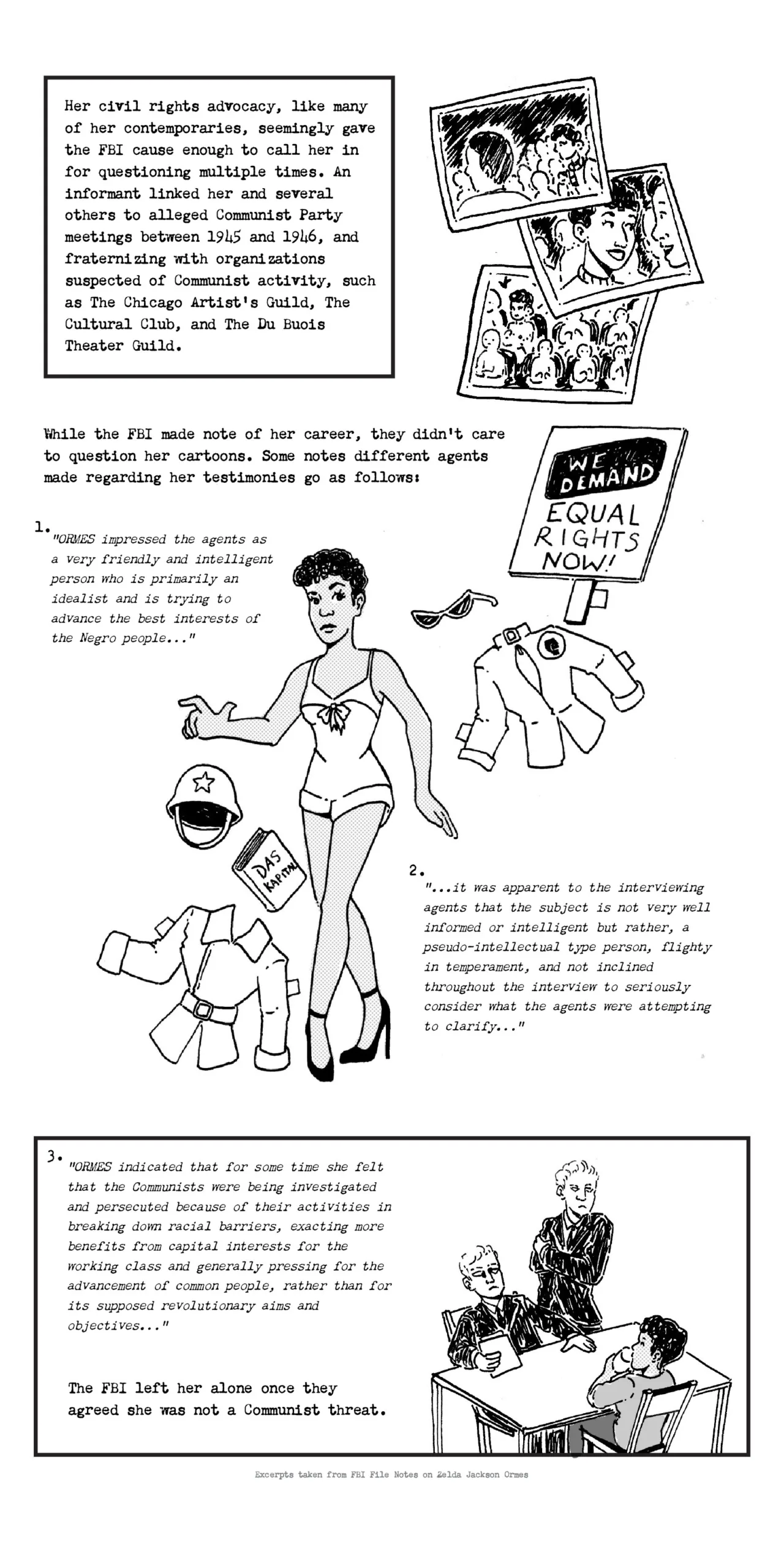

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum – Nancy Goldstein Collection on Jackie Ormes. Original box with the FBI/Justice Dept. file on Jackie Ormes.

Kenneth B. Clark & Mamie P. Clark, “Emotional Factors in Racial Identification and Preference in Negro Children,” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 19, No. 3, Summer 1950. Accessible via JSTOR.

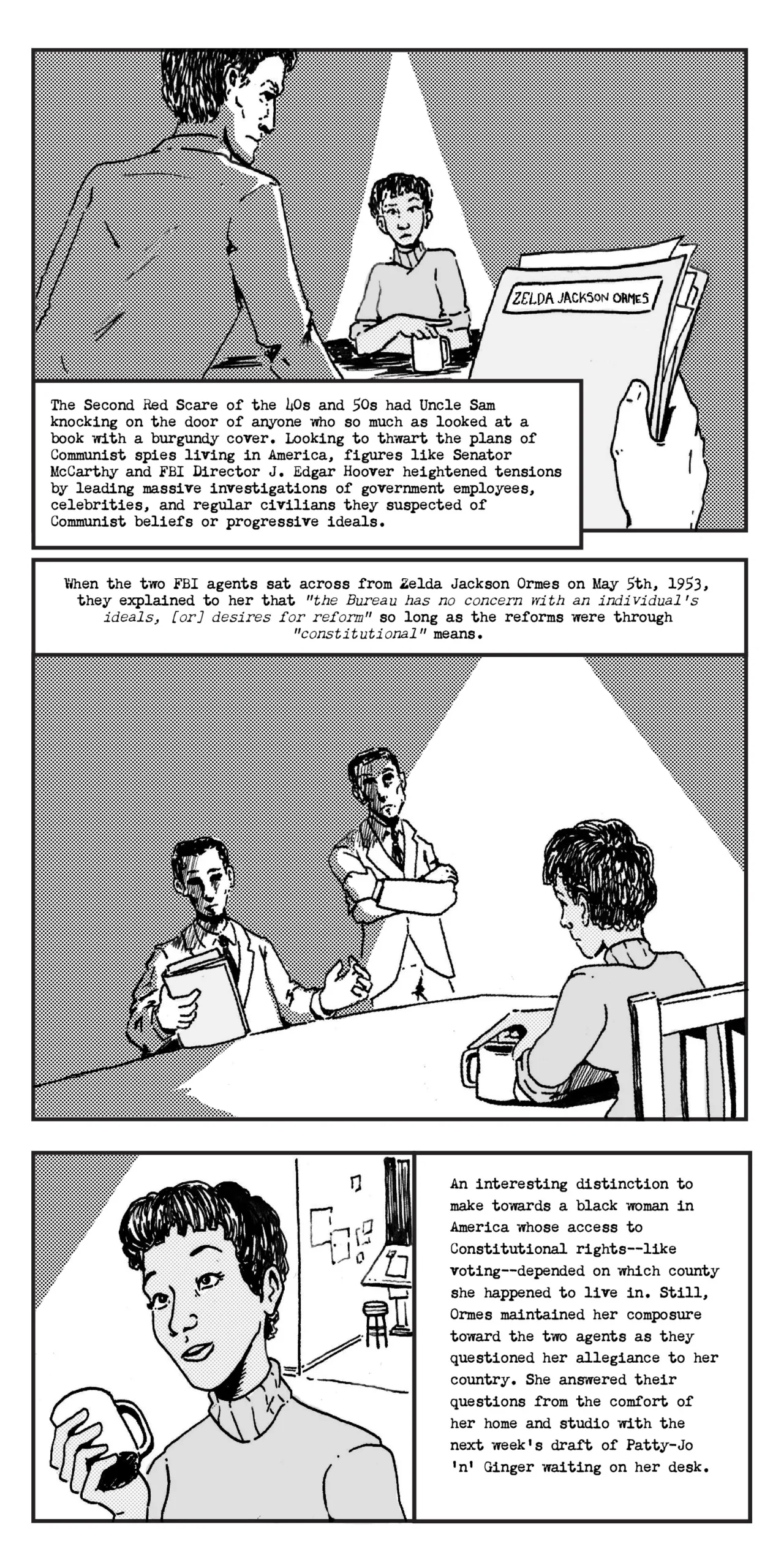

Nancy Goldstein, Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist, University of Michigan Press, 2008.

Gordon Parks photography featured in “Problem Kids,” Ebony, Vol. 2, No. 9, July 1947, p. 20-21. Information available at the Gordon Parks Foundation.

South Side Community Art Center Website, sscartcenter.org.